Errol Morris’s Tabloid invites audience participation.

The audience is tasked with the job of questioning the subject’s reliability as a narrator. Subjectivity emerges as an inevitable theme throughout Morris’ body of work as a natural extension of the Interrotron format, where the subject delivers the narrative in their own words while looking directly into the camera lens, making eye contact with the audience. Part of Morris’s brilliance is his confidence in the audience’s natural skepticism.

Take a lesser documentary for instance, Jesus Camp, whose makers had the good fortune to happen upon some great copy: fundamentalist zealots indoctrinating children to pray for George Bush and condemn Harry Potter as liberal Wiccan propaganda. That footage could’ve edited itself. But rather than let the viewer draw its own conclusions about the moral ambiguity of forcing dogma on impressionable minds, the makers chose to point their cameras at an outraged moderate Christian talk radio host who expressed exactly what’s wrong with forcing dogma on impressionable minds. The work is practically done for us.

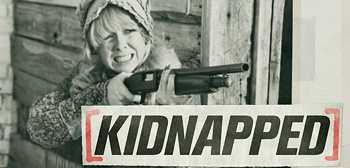

Morris offers no such easy disambiguation. In Tabloid, we are presented with two sides of a story. On the one hand, we have Joyce McKinney, who allegedly kidnapped a Mormon missionary with whom she was obsessed, shackled him to a bed in the English countryside, and forced him to eat southern-fried chicken and fuck seven times over the course of three days. According to Joyce, she was only trying to deprogram the Mormon brainwash from his mind with sex. The handcuffs were just a curative for the impotency. She fondly recollects the long weekend like it was her honeymoon. Even if we give her the benefit of the doubt on that one, she doesn’t make much of a case for why she flew to England in a private plane, armed with a fake gun and a bottle of chloroform.

On the other hand, we have two deliciously unapologetic representatives of the British gutter press who covered the story for the Daily Express and the Daily Mirror. To hear them tell it, well, who gives a goddamn if the facts were straight? This story had a ribbon on it. And that’s even before she genetically cloned her puppy.

So through door number one we have a woman whose idea of a honeymoon involves forcible restraint, and through door number two we have the paparazzi, the only profession on earth that scores below politicians on the trust-o-meter. Where’s a levelheaded radio commentator when you need one?

The subjects themselves acknowledge the viewers’ dilemma. In one story, she’s a saint. In the other, she’s a whore. The reality was probably somewhere in-between. Problem is, we don’t know what really happened. And Errol Morris spins that problem into a great cinematic riddle.

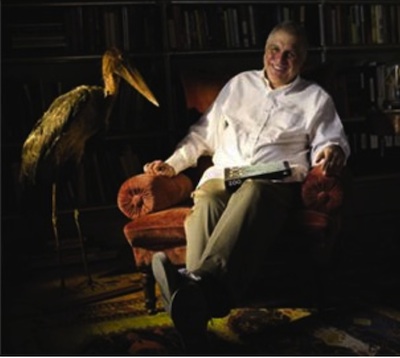

But you knew that already. This isn’t the director of Heaven’s Gate, it’s the director of Gates of Heaven. If he ever makes a bad film I’ll eat my shoe. You don’t need me to tell you that the sky is blue, someday you’re gonna die, and Errol Morris is a genius. I do, however, have something worth sharing about Joyce McKinney.

Early in the film, McKinney says, “I never saw much of the world, until I went to Utah.” To the audience with which I screen the film, at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, this is funny.

The rolling guffaws are so intense they drowned out the next two lines of dialogue. Everything my conservative uncle had to say about my adopted city is revealed to be true. We really are condescending. We really are evil. And I’m no better, because I catch myself laughing at McKinney a moment later when she extolled the virtues of beauty pageantry.

The rolling guffaws are so intense they drowned out the next two lines of dialogue. Everything my conservative uncle had to say about my adopted city is revealed to be true. We really are condescending. We really are evil. And I’m no better, because I catch myself laughing at McKinney a moment later when she extolled the virtues of beauty pageantry.

I mention this because Morris has a reputation in some circles for having fun at the expense of his subjects. He lets his subjects squirm in the hot seat and dig themselves as deep a hole as they can for the express purpose of proving his intellectual and moral superiority over them. This doesn’t apply to Robert MacNamara (whom some say Morris let off the hook) or Stephen Hawkings, because in those films Errol Morris is telling us that he finds his intellectual equals at the pinnacles of our society. But when we bear witness to Fred Leuchter’s stupefying anti-Semitism in Mister Death, or Rick Rossner’s compulsive need to engage in do-overs in One in a Million Trillion, we are supposed to know that they’re no match for the man on the other side of the lens. In other words, Errol Morris wants you to know that he has a big dick.

I mention this because Morris has a reputation in some circles for having fun at the expense of his subjects. He lets his subjects squirm in the hot seat and dig themselves as deep a hole as they can for the express purpose of proving his intellectual and moral superiority over them. This doesn’t apply to Robert MacNamara (whom some say Morris let off the hook) or Stephen Hawkings, because in those films Errol Morris is telling us that he finds his intellectual equals at the pinnacles of our society. But when we bear witness to Fred Leuchter’s stupefying anti-Semitism in Mister Death, or Rick Rossner’s compulsive need to engage in do-overs in One in a Million Trillion, we are supposed to know that they’re no match for the man on the other side of the lens. In other words, Errol Morris wants you to know that he has a big dick.

Proponents of this theory will find no rejoinder in Tabloid. With the exception of the South Korean genetic biologist that electroshocks canine skin cells into spontaneous life, Errol Morris probably is smarter than everyone on screen. He probably knows it, too. To make matters worse, he has made a very funny film about these people rather than a sober case study. He’s telling you it’s okay to laugh at them because he’s laughing at them, too.

I don’t buy that bullshit. Morris shows bottomless empathy for his subjects. When Rick Rossner explains that he hasn’t dropped his complaint about being given a bum question on Who Wants to be a Millionaire?, Morris doesn’t pass judgment when he asks, “Why not give it up?” It seems like he wants to understand why Rossner is torturing himself. He doesn’t even seem to hate Leuchter for being a Holocaust denier, and you are allowed to hate someone for being a Holocaust denier.

The point of Mister Death, One in a Million Trillion, and, I would argue, Tabloid, is to show you how to empathize with someone that seems below your threshold for empathy.

So the lights come up.

The way to the exit is blocked. It seems the entire crowd has gravitated towards a large blue singularity towards the back of the theater. Then, faintly: “I didn’t want you to recognize me when I came in so I wore a pair of sunglasses and a hat.”

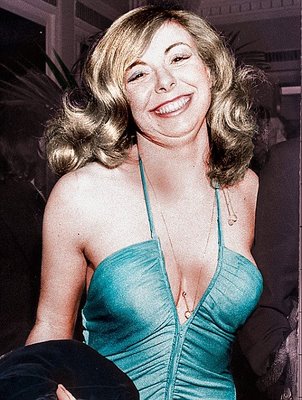

The costume had been discarded. There she is, the fleshly incarnation of our collective gaze for the past ninety minutes, Joyce McKinney, in all her glory. If she didn’t want to be recognized, it seems an odd decision to wear what was very nearly the same dress she wore on camera.

That’s the first thing that goes through my head. Even though she insists that the tabloids ruined her life, there’s still a part of her that desperately needs to be in the spotlight. But never mind the motivation, Joyce McKinney has come to the Museum of Modern Art to set the record straight. She is going to sue Errol Morris.

As I drag my girlfriend through the crowd to get a better view, I try to imagine myself in her shoes, sitting in the back of that theater. One moment she has the entire audience in stitches because she wasn’t well-traveled enough for their liking, and the next a tabloid journalist calls her ‘barking mad,’ without rebuttal from his interrogator. Joyce probably found Errol Morris to be a sympathetic ear, but this final product must have felt like a betrayal. What if Errol Morris was laughing at her? A hot twinge of guilt creeps up my spine. I never had occasion to consider how, for instance, Fred Leuchter felt after seeing Mister Death, but the thought is inescapable now. This lady is crying.

A high pitch feedback loop from a hearing aid drowns out the voice from across the room as I turn to see an old woman turn a screw in her ear with her fingernail. “Whaaaat’s going on? Who is that?”

I kneel down to her and whisper, “It’s the woman from the movie, ma’am. She’s in the theater right now, and she has something to say.”

She looks at me with an expression that could fry an egg. Apparently, the prospect of spending one more minute in the company of the subject of the preceding abortion is about as appealing as a hammer to the face, so she pushes past me towards the back of the crowd in search of a fire exit.

Joyce wipes a tear from her cheek and holds up a fraying Mead folder, yellow with zig-zagging stripes, that contains signed contracts, indisputable evidence, a paper trail that she would be all too happy to show you before she tucks it back into her purse. “One of my worst faults is that I am too trusting of people.”

I realize I like Joyce McKinney. In the movie, Morris asks her if she believes it is possible for a woman to rape a man and her response is, ‘That’s like putting a marshmallow in a parking meter.” Not every laugh was at her expense. And even though I don’t really believe everything she said, I want to. Here’s a woman that just wanted to tell a very special love story, but it was perverted into a meditation on obsession. Maybe Errol Morris did misrepresent her, parade her as another attraction in his unfolding freak show to be scrutinized through a lens and then discarded as a liar and a sexual deviant like she was so enthusiastically portrayed by the British gutter press.

I suddenly become the head cheerleader in the Joyce McKinney booster club. Ball’s in your court, Joyce. Tell me why I shouldn’t trust Errol Morris.

It all started when she was confronted by Showtime to do a television show. Did you know that Penthouse magazine once offered her two thousand dollars for her pictures? She survived a hurricane. Her poor mother just died. If you slow down the film, you can clearly see that they pasted her head onto another girl’s body. They told her that Errol Morris won an Academy Award. Children and dogs love her.

It all started when she was confronted by Showtime to do a television show. Did you know that Penthouse magazine once offered her two thousand dollars for her pictures? She survived a hurricane. Her poor mother just died. If you slow down the film, you can clearly see that they pasted her head onto another girl’s body. They told her that Errol Morris won an Academy Award. Children and dogs love her.

It goes on like this for a while. She breaks down into tears, then abruptly laughs as quickly as she changes subjects. The crowd grows restless and thins. One man accuses another with a British accent of being a reporter for the Daily Mirror. My girlfriend inches towards me and delicately grasps my fingers. “Do you want to stay?’” I do.

A woman asks Joyce why she ever agreed to sign the releases. Joyce warns it’s quite a story, but dog lovers might not want to listen. She had a dog that was in a cage on death row. A man climbed over her fence and shoved a stack of papers in her face. He cruelly dug a ball-point pen into her hand. “You can still see the scars.” Joyce takes a deep breath. “And he said– pardon my language, Lord forgive me– ‘Sign that goddamn contract or that dog is gonna die.’”

Now I feel guilty again, but for a different reason this time. Listening to Joyce is exhausting. My girlfriend asks me again, “Should we stay?” I don’t know what I want, but I have a clearer perspective than before.

Joyce McKinney felt that Errol Morris twisted her words and turned her into a freak because it made for a more interesting story. The truth is, Errol Morris did twist her words. He sifted through them, what must have been a multitude of them, and stitched them back together to present the most truthful Joyce that Joyce could be. He made her witty, likable, and romantic. Above all, he made her a tragic figure of her own invention.

The editing of Errol Morris’s Tabloid was an act of empathy.

A MoMA administrator pipes in. She’s sorry, but they have to close the museum. We’ll have to take this outside. Joyce doesn’t mind. She cheerfully offers, ‘You can follow me to my limo, and I’ll show you the clones.’

With that, my girlfriend and I agree that we’d drunk our fill, but while I waited for a security guard to retrieve my backpack from the bag check, I saw Joyce one more time.

Most of the crowd had disbursed, but some remained, smoking cigarettes by the back door and exclaiming how what they just witnessed was ‘insane!’ Joyce emerged through a plate glass door with some of her more enthusiastic boosters that hung on to her every word. She had had a long day and was walking in her nylon stockings, two-inch heels in hand. Not to put it indelicately, but while, in her youth, Joyce was ‘as tiny as a pout,’ in her current physical condition, she had grown quite a bit bigger.

One of the stragglers, a man in green and brown jungle print pants speckled with bright red flowers, broke away from his group and circled around Joyce to her back. Joyce didn’t notice him. She had a huge smile on her face and waved her arms wildly as she went on about her dogs to a captive audience.

The man quietly slid his iPhone from his pocket, turned on the camera, and dropped to one knee. He slowly extended his arm and framed up a shot of Joyce’s ankles. They were knobby and bloated, and he had a good look at them without the shoes on. Click.

When he stood up, he saw me looking at him and we made eye contact.

‘Really?’ I said.

He gave me a fuck-you scowl and stomped off.

If I wasn’t a coward, I could have kicked the phone out of his hand. I didn’t, so I’m no better than him: just another spectator in the theater of human misery. I wonder if there was another man behind me, and I wonder if he felt the same disgust for me as I felt for the picture-taker as he watched me watching him watching her.

Joyce left. The attendant returned my backpack and my girlfriend and I exited the building. Across the street, a crowd had formed around a black Lincoln Towncar. I told my girlfriend that we should check it out. She asked why, and I said, ‘Maybe we’ll see the dogs.’

We approached the crowd. Joyce was smiling, but I didn’t see any dogs. As we left for the subway, flickers of light hit Joyce from every angle, but there were no flashbulbs. They came from milky white LEDs, built into the backs of cellular phones.

I wished my phone had a flash.

Scott Cipu is a freelance film critic.